The word "Fishrot" alone evokes the foul stench of corruption.

The financial scandal, which was given the "Fishrot Files" moniker after a 2019 Wikileaks release, spans from Namibia to Iceland, involves government ministers and at least $20 million (£16.76 million).

The nation of southern Africa is currently getting ready for the largest corruption trial in its brief history.

Fish quotas are the main issue; although they may not seem like an obvious source of corruption, they are very profitable in Namibia.

Fishing is one of the nation's main industries and generates about 20% of export revenue thanks to its nearly 1,600km (1,000 miles) of South Atlantic coastline.

In the Fishrot scandal, a number of prominent politicians and businessmen are accused of executing plans to seize control of lucrative fishing quotas, such as those held by the state fishing firm Fishcor. Then, it is claimed, they transferred them to the Icelandic fishing firm Samherji in exchange for kickbacks.

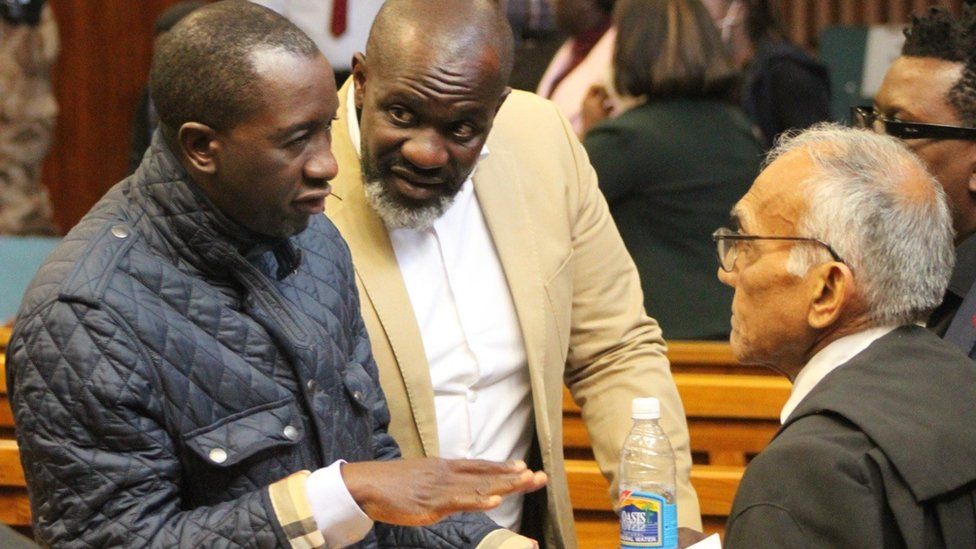

Ten suspects are suspected of having benefited, including former Justice Minister Sakeus Shangala and former Fisheries Minister Bernard Esau.

All those accused, some of whom have been held in custody for more than three years, have adamantly maintained their innocence. One of Iceland's most significant companies, Samherji, has vehemently refuted claims of bribery.

The wider Namibian fishing industry has also suffered because of the scandal. Jobs have been lost and government revenue has decreased; these funds could have helped the most vulnerable members of one of the world's most unequal societies. .

First, a portion of Fishcor's earnings were supposed to fund social programs like drought relief and job training. Second, because the fishing quotas were misdirected, the entire Namibian fishing industry suffered.

A former Samherji manager in Namibia named Johannes Stefansson released over 30,000 documents, including business emails, contracts, presentations, and photos, to WikiLeaks in November 2019. This is when the scandal first surfaced. He claimed that the business had conspired with a number of powerful individuals to obtain access to the fishing quotas at a discount from their market value.

This has turned out to be a complicated case, and the lengthy legal process will likely end up in court soon, but it is also having an effect in the real world.

This can be observed in places like Walvis Bay, the country's main harbor.

Jason Ipinge resides in Narraville, one of the main townships in Walvis Bay, where one-story houses encroach all the way to the desert's edge.

Back in 2018, he was laid off from one of Samherji's large factory trawlers.

One of Samherji's subsidiaries had leased the ship, the Heinaste, to a regional joint venture company, ArcticNam, which brought three Namibian quota holders and a large quantity of fish with it.

It seems like things between the partners soured after a few successful years. It has been reported that there was a disagreement over whether the promised jobs had materialized between the Namibian and Icelandic sides of the business.

The entire crew was ordered to leave the ship without warning or explanation, according to Mr. Ipinge, and the fishermen working on the boat weren't even aware that things had turned toxic.

He said, "I've lost a lot in life, and my dignity has also been damaged. "In the past, I was able to support my parents back in my village, but I'm unable to do so any longer. " .

The tale of Mr. Ipinge is not at all unusual. Several people in a comparable situation were interviewed by researchers Ellison Tjirera and Rui Tyitende from Namibia's National University.

Mr. Tjirera says, "We heard stories of people who had to pull their kids out of school and send them to their grandparents, stories of people who lost their partners because they couldn't support their families any more.".

A few turned to crime. So I think you can understand how this massive corruption scandal affected the lives of regular people. ".

Unsurprisingly, a large number of businesses suffered in Namibia's competitive fishing industry. Fishcor's business practices were questioned, which may have had an impact on people who may not have been involved in the scheme.

One of the largest fish factories in sub-Saharan Africa, Princess Brand Processing (PBP), is still having trouble.

PBP captures and transports horse mackerel, a species that is widely available on the African market, to shore for processing. According to general manager Adolf Burger, it has adopted a labor-intensive strategy that has generated 650 jobs.

This is carried out with 10 or 15 people in Europe, according to Mr. Burger. It was possible to build a fully automated factory in this location, but since the goal is to create jobs, we kept it as manual as we could. ".

A significant quota allocation that had been agreed upon with Fishcor was lost by the company when the Fishrot scandal broke.

When Namibia gained independence 33 years ago, it was with the hope of finally claiming its abundant marine resources—which had been used for decades by other countries—that jobs and prosperity would be created for Namibians.

A policy of "Namibianization" was implemented by the new administration, which was led by the former liberation movement turned political party Swapo (South West Africa People's Organisation). This included granting fishing rights to the nation's residents and requiring foreigners seeking access to its resources to enter into joint ventures.

Graham Hopwood, executive director of the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) in Namibia, claims that despite having good intentions, a policy has encountered difficulties.

"Companies that are Namibian, or have a majority Namibian ownership," he says, "are given the rights to various different types of fish in our sea on extended periods of 10, 15 years and so on.

"That, in theory, is good, but most of these are just briefcase businesses that exist only on paper, frequently owned by people who have no experience fishing and no infrastructure but see this as a way to make money; many of these people also have political connections. ".

The IPPR is not the only organization that believes that the industry is vulnerable to abuse because of the opaque way it is run and regulated. .

Later this year, when the Fishrot case finally goes to trial, it will be the largest trial in the history of the nation.

Racketeering, bribery, money laundering, and tax evasion are among the allegations made against the suspects in the 144-page indictment.

Additionally, it is alleged that the defendants manipulated a bilateral cooperation agreement with Angola to divert more quotas to Samherji at extremely low prices.

A political price was also associated with the scandal.

Only a few days after the Fishrot story went viral, Swapo experienced its worst election results.

Rui Tyitende, an analyst, states that "politically they are in the intensive care unit.".

Iceland's reputation as a whole, which has declined in the past few years according to the global corruption index, is also being scrutinized, not just that of one of the most significant companies there.

Allegations of bribery have consistently been refuted by Samherji. When the scandal first surfaced, it hired a Norwegian law firm to look into it. The company released a statement after receiving the report in which it acknowledged the problem but insisted there had been no bribery.

The way payments were made, to whom they were made, and on what basis, as well as who had the power to give instructions about them and where they should be received, Samherji said, all required closer attention. "It is also obvious that the underlying contracts for the payments should have been formal and precise. " .

The business added that it had taken significant steps to prevent similar errors from happening again.

It holds the whistleblower, Johannes Stefansson, accountable for any criminal activity that may have taken place.

However, Mr. Stefansson claims that other people authorized the payments, and he is expected to be the prosecution's key witness at the trial later this year.

Fishrot: Clear Waters, Murky Dealings is a BBC World Service documentary worth listening to.