It is completely off topic for more than 100 world leaders to promise to stop clearing forests. new research suggests.

In comparison to 2021, the year the agreement was signed at a UN climate conference, more of the world's older, carbon-rich tropical forests were cleared or burned in 2017.

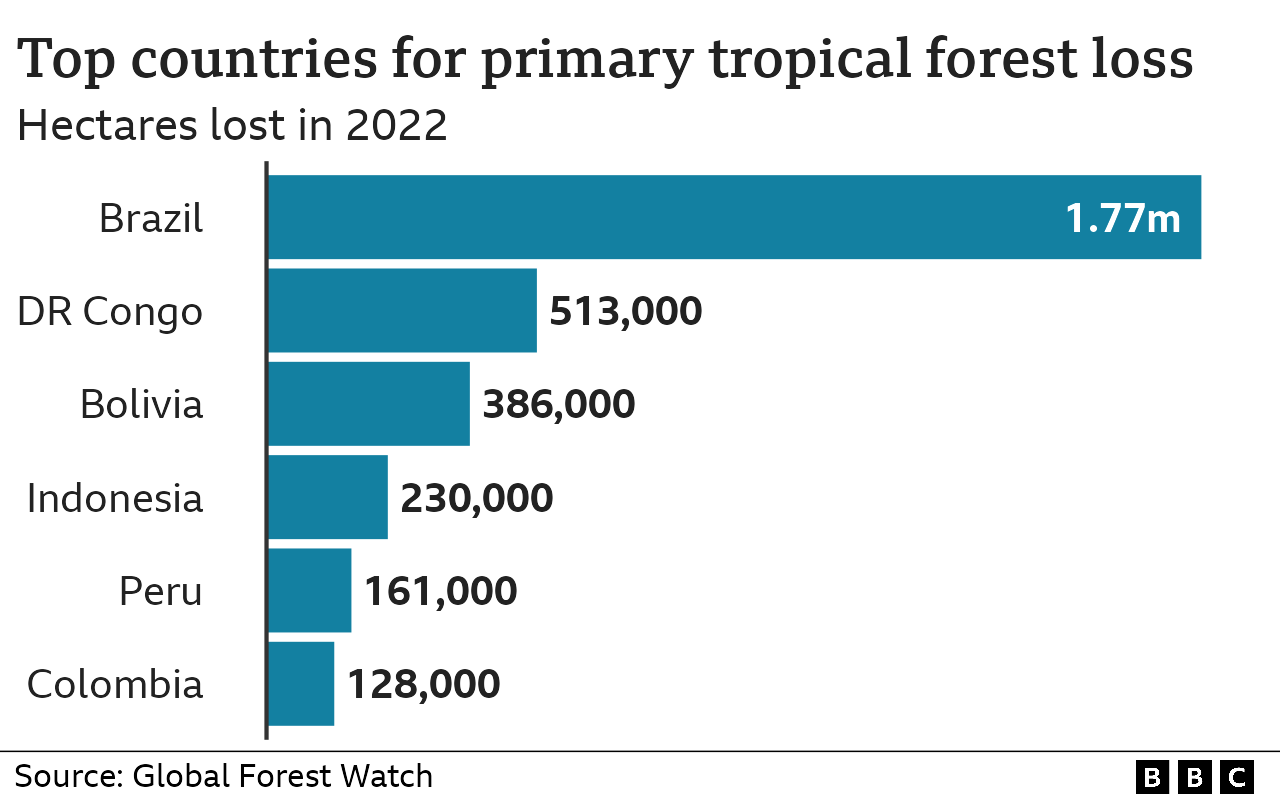

Brazil led the deforestation in 2022, losing an average of 11 football fields of forest per minute.

However, a significant decline in forest loss in Indonesia demonstrates that this trend can be reversed.

Over 100 world leaders came together to sign the Glasgow Declaration on Forests at the COP26 climate conference in 2021. In it, they pledged to work together to "halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030." This was one of the meeting's most significant moments.

Leaders from nations that account for about 85% of the world's forests joined in total. Among them was Jair Bolsonaro, the former president of Brazil, who had loosened the enforcement of environmental laws to permit development in the Amazon rainforest.

Following the failure of a prior agreement signed in 2014 to stop the unrelenting loss of trees, the Glasgow pact was reached.

The new promise made in Glasgow isn't being kept, according to a new analysis by Global Forest Watch.

It is thought that the loss of tropical primary (old-growth) forest is especially important for biodiversity and global warming.

Huge amounts of greenhouse gases are absorbed by the rainforests in Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia.

By removing or burning these older forests, carbon that has been stored in them is released into the atmosphere, raising global temperatures.

The preservation of biodiversity and the livelihoods of millions of people depend on these forests.

Because these forests have grown over such a long time, scientists caution that these functions, or "ecosystem services," can't be easily replaced by planting trees elsewhere.

According to the most recent data, gathered by the University of Maryland, the tropics lost primary rainforest by 10% more in 2022 than in 2021, totaling just over 4 million hectares (nearly 16,000 square miles) in total cut down or burned.

The amount of carbon dioxide that was released was equal to India's annual emissions from fossil fuels.

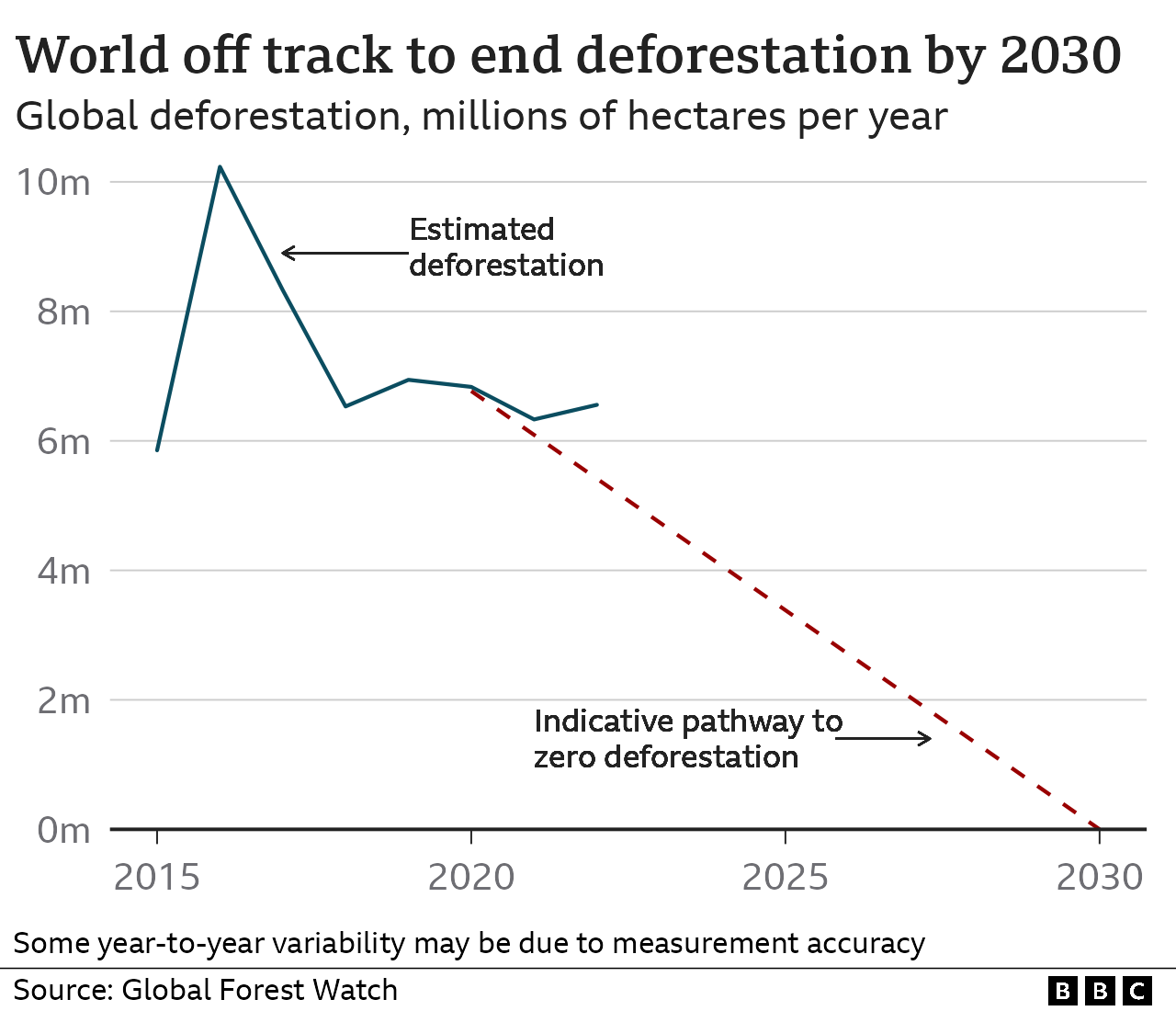

The short answer to the question, "Are we on track to end deforestation by 2030?," is categorically "no," according to Rod Taylor of the World Resources Institute (WRI), which manages the Global Forest Watch.

"On a global scale, we are badly off course and moving the wrong way. Our analysis reveals that in 2022, global deforestation was more than 1 million hectares higher than what was required to be on track to achieve zero deforestation by 2030. ".

Brazil is the country that loses the most primary tropical forest, and in 2022, this increased by more than 14%.

Over the past three years, the rate of deforestation in the Amazonas state, which is home to more than half of Brazil's intact forests, has nearly doubled.

The loss of forests accelerated quickly in 2022, increasing by almost a third in a single year, and Bolivia, one of the few nations to not sign the Glasgow Declaration, also experienced this trend.

Commodity agriculture is the main driver, according to researchers. Soybean expansion has resulted in nearly a million hectares of deforestation in Bolivia since the turn of the century.

Even though Ghana in West Africa only has a small amount of primary forest left, there was a significant increase in losses in 2022 of 71 percent, mostly in protected areas. Some of these losses are close to existing cocoa farms.

Despite the overall gloom, there have been some encouraging developments that demonstrate that deforestation can still be controlled.

Since reaching an all-time high in 2016, Indonesia, more than any other nation, has decreased its primary tropical forest loss.

Analysis suggests this is down to both government and corporate actions.

In 2019, efforts to monitor and control fires were stepped up, and there was a permanent ban on logging in new palm oil plantations.

It's a similar story in Malaysia. In both countries, oil palm corporations also appear to be taking action, with some 83 percent of palm oil refining capacity now operating under no deforestation, no peatland and no exploitation commitments.

With a new president in Brazil committing to end deforestation in the Amazon by 2030, there is renewed hope that the promises made in Glasgow in 2021 might fare better in the coming years.

But if the world wants to keep global temperatures under the critical 1.5C threshold, the time for action on forests is very short indeed, say the researchers.

It is more urgent to achieve a peak and decline in deforestation than a peak and decline in carbon emissions, according to Rod Taylor of the WRI.

"Because once you lose forests, they're just so much harder to recover. They're kind of irrecoverable assets. ".

The loss of tree cover can be monitored relatively easily by analysing satellite images - although there's sometimes uncertainty about the precise year in which trees have been lost.

Measuring deforestation - which typically refers to human-caused, permanent removal of natural forest cover - is more complicated, because not all tree-cover loss counts as deforestation.

For example, losses from fire, disease or storms, as well as losses within sustainable production forests, would not usually count as deforestation. This presents challenges; for instance, some fires may have been intentionally started to clear a forest as opposed to being natural.

Scientists try to take all of these factors into account to come up with an estimate for deforestation.

The latest figures suggests a rise in (human-caused) global deforestation of about 3.6 percent in 2022 compared with 2021 - the opposite direction to what was pledged in Glasgow.

Interestingly, whilst losses of the particularly important primary tropical forests rose by nearly 10 percent in 2022, overall global tree cover loss from all causes actually fell by nearly 10 percent.

But researchers say this was because losses from forest fires were down in 2022, particularly in Russia. This is not thought to be part of a long-term trend.

In fact, tree cover losses from fires have generally increased in the last two decades, and fires are expected to become more common in future due to climate change and alterations to the way land is used.

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc.